A major shake-up in building product regulations, aimed at making construction easier and more affordable, is on the way, announced Building and Construction Minister Chris Penk at the Auckland Home Show in early September.

The Minister revealed that the Coalition Government has introduced the Building (Overseas Building Products, Standards, and Certification Schemes) Amendment Bill, with the aim of improving access to a wider range of quality building products from overseas, “giving Kiwis more choice and injecting competition into the market.”

“We know that our building system lacks competition and that it’s too expensive to build in New Zealand,” Penk said. “The building supply chain is dominated by a few big companies, which makes us vulnerable to price increases, supply chain disruptions, and shortages.

“This lack of competition, even in business-as-usual situations, results in more expensive building products and less innovative and efficient building processes. As a result, Kiwis pay exorbitant construction costs and face long waits for building work.

“It is unacceptable that building a standalone home in New Zealand is about 50 per cent more expensive than in Australia,” he said.

The new Bill introduces changes to the Building Act that will reduce barriers to using quality overseas building products in New Zealand by enabling recognition of overseas standards and certification schemes, thus removing the need for designers, builders, or Building Consent Authorities (BCAs) to verify standards.

Penk said this will streamline the citation of international standards with the new Building Product Specification, which can be used alongside Building Code documents to demonstrate compliance. It will also require BCAs to accept building products certified overseas and recognised by the regulator, the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE).

But what does this mean in practice?

Andrew Moore, Commercial Manager at CMP Construction Ltd, notes that some imported building material costs have dropped significantly since the post-COVID surge (for example structural steel, reinforcing), but, as the Minister highlighted, limitations in materials and suppliers in some areas are still driving inflation and restricting builders’ options.

Moore is excited by the possibility of using more advanced products and construction techniques from overseas that were previously restricted by regulations. He believes (as an example) mass timber construction is an area ripe for improvement.

CMP Construction mass timber structure at Highbury Triangle, Auckland

“The issue here is that there are limited manufacturers that supply the components used in mass timber construction, and when you look at the cost of those buildings, they can be quite different to what you see with traditional concrete and/or steel,” he says. “The key to reducing those costs is bringing in more competitive products from overseas.”

But what challenges does Moore foresee in implementing this change?

“The key from our perspective is unblocking compliance pathways, whether it’s a BRANZ appraisal, Council acceptance of these products, or simply being able to specify them directly from the supplier.

“Obviously, Councils need to be confident they can issue building consents for these products without risking long-term problems. So, the challenge lies in ensuring a fast, proper, and robust process to get these new products approved and consented,” he says.

With new suppliers potentially importing products more easily, Moore sees a risk that some businesses may not commit to maintaining stock levels or supply chains over time. And he says that changing a specified product on a large project isn’t easy, should the new supplier pull out of the market.

CMP Constructions Hyde Lane Apartments, Wellington

So, does this mean that, even if central government directs officials to ease the importation of building materials, Councils could still create roadblocks that make it just as difficult as before?

“I fully support having robust processes and ensuring good products are specified and consented. However, the pathways to get a project consented need to be fast, and those bringing in new products need the opportunity to get specified and set up easily otherwise, we’ll just see a repeat of what’s happened in the past,” he said.

“A project is only viable if it’s made feasible, and banks won’t lend money on a project unless certain thresholds are met regarding viability, margins, and contingencies.

“We need to bring down the cost of building materials to support local businesses and the New Zealand workforce. There is a balance to be struck,” Moore says.

But what standards should we recognise? It’s not as simple as saying ‘one country’s standards are good and another’s are bad,’ he says.

“We’re involved in several projects where we are sourcing pre-manufactured components from overseas, with local Council approval. As long as there are quality control processes in place, certified and legitimate people to ensure products meet the consented standard, and design specification – it’s not that difficult, and we’re already doing it.”

“If Chris Penk is going to do anything, I think the first step is to address the compliance pathways. Assemble a panel of passionate people who want to make this work without all the roadblocks and open up the industry so we can reduce construction costs and make building more feasible for everyone.

“New Zealand is one of the most expensive places in the world to build. Labour is one component, but compliance pathways slow down New Zealand approval processes and create an unattractive place to bring goods into because it’s just too hard,” Moore said.

Alex Greig, Director of GreenHAUS Architects has focused on more ecologically sustainable forms of building throughout his career in New Zealand. As a result, he has faced the limitations of the product certification process more than most.

He’s spent eight years trying to gain approval for a prefabricated fibreglass module that forms the shell of an earth-sheltered house, and efforts are ongoing. Currently, he’s seeking Council consent for a project featuring a conservatory manufactured and supplied by a German aluminium specialist.

Fibreglass earth-sheltered house module

“This company produces countless conservatories and windows installed across Europe, all engineered to withstand the climates and conditions of their locations,” says Greig.

“Their conservatories are in extreme locations in the Alps, with very high wind zones. Yet, in Upper Hutt, this conservatory project has been with the Council for at least eight months and is still awaiting consent.”

Despite having detailed information and design certificates, the conservatory will require a bracing schedule commissioned from a New Zealand engineer which will cost around $20k, and without this, Greig says the Council is signalling a likely rejection.

His next step will be to seek a determination from MBIE, but even if granted, more than eight months and tens of thousands of dollars will have been lost.

Greig is keen on the changes to the Building Act outlined by Minister Penk. “In principle, it’s fantastic. Let’s get it over the line,” he says. But how will New Zealand authorities assess these imported products without resorting to the same red tape that exists now?

“The Bill mentions accepting products that comply with overseas standards ‘equivalent to or higher than those in New Zealand.’ We need to ensure the products meet our quality standards and that the overseas testing processes and documentation proving this have integrity,” he says.

“But, going back to the earth-sheltered house project, these have, these have already been built in the Ring of Fire nations like Hawaii, the US Marshall Islands, Ecuador, Puerto Rico – all places with massive earthquake possibilities. And they also meet The International Building Code. So, if we can just accept The International Building Code here, then they should automatically be able to be built!” he says.

“It’s a really interesting conversation to be had. Why do we need a local New Zealand building code? And why can’t we just adopt a global one because the global one is there to protect the same motivations?

“Why do we need to re-invent the wheel so much, with our own testing standards. We have 4.5 million people, and we have 67-odd territorial authorities where Sydney, a city of 5 million people has one territorial authority for building consents.

“The energy and money that goes into supporting those 67-odd territorial authorities potentially can be reduced. I think definitely one building consent office for all of New Zealand would be a good move,” he says.

Greig also highlights that no system is foolproof. He’s had plenty of experience with potential issues.

“When dealing with international products, it’s like buying clothes online – it’s hard to claim a refund or compensation for defective products. It’s crucial to ensure products meet our standards and perform well in New Zealand conditions,” Greig says.

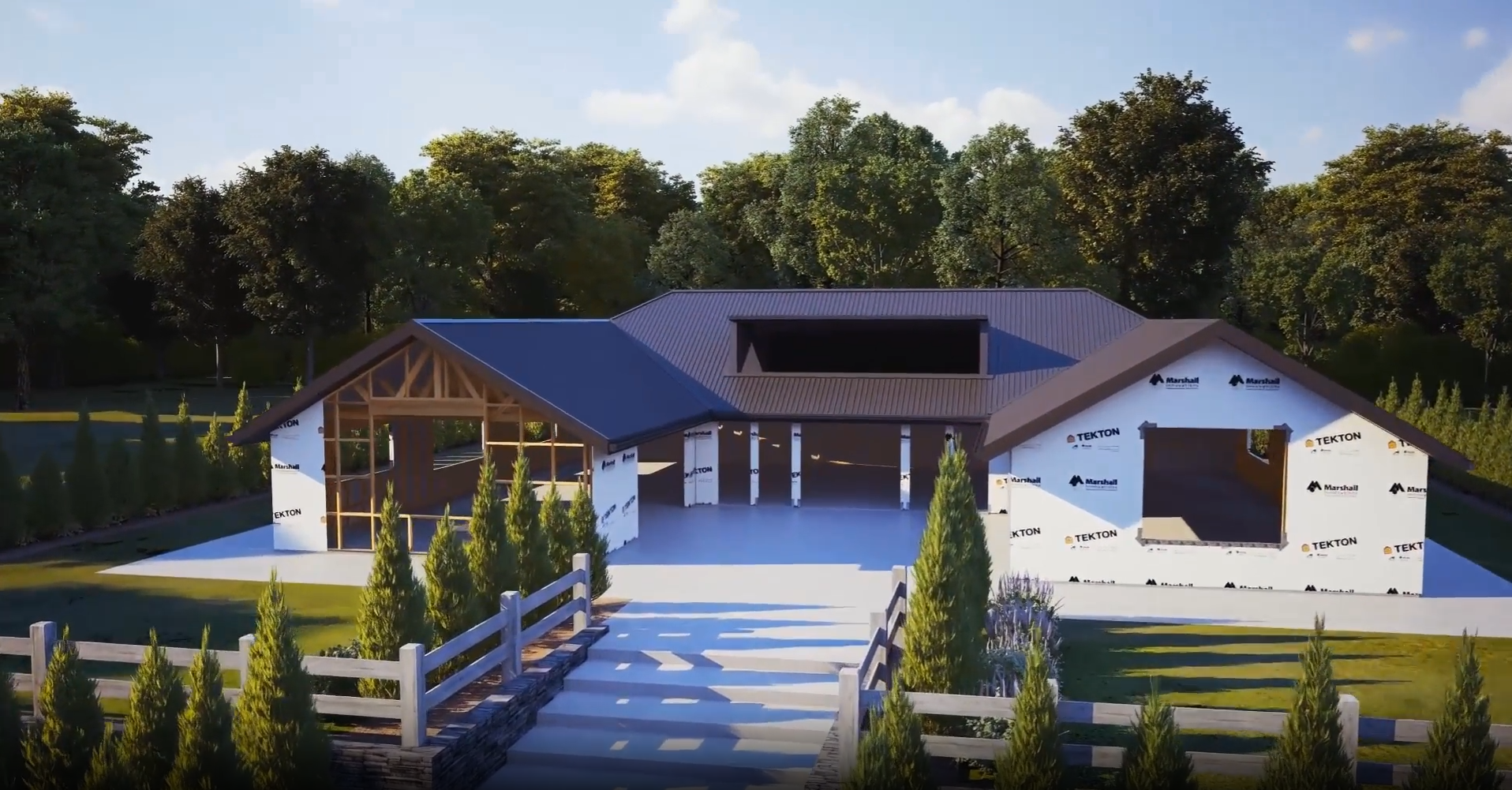

Israel Ellis, National Sales & Marketing Manager for Marshall Innovations, a company specialising in cutting-edge products such as breathable weather barriers and mass timber construction components, sees many products overseas they could bring to the New Zealand market.

However, the financial burden of re-testing each product for the local market is prohibitive, especially without certainty about the product’s market potential.

“It’s a slippery slope. While we support reviewing products that have undergone rigorous testing from globally recognised authorities, we still believe New Zealand needs a robust standard to ensure we’re not just letting any product into the market,” he says.

The Marshall Weatherization System

Ellis notes that working at the cutting edge of innovation means constantly testing new products. “We’re continually reviewing our own products, but we must be careful about what we introduce to the market – healthy homes are the ultimate goal and that is at the forefront of our business,” he says.

“What concerns us is the potential for companies looking to make a quick cash grab by importing inferior products. New Zealand could become an easy avenue for substandard materials,” Ellis warns.

He also raises concerns about products with fraudulent or mislabelled certifications. “The construction and building industry require products that meet New Zealand regulations. We must ensure that overseas testing authorities have equivalent requirements.”

When it comes to reliable international standards, Ellis suggests Europe as a good starting point. “Countries like Germany, England, and other Scandinavian nations have high standards, as do the US and Canada. But how will the Government determine which standards are better than ours? And how will they ensure alignment between Councils and other regulators?

“There are many unanswered questions. Ultimately, we need everyone working from the same playbook,” Ellis says.

Who Takes the Risk?

So, while many of those interviewed by Industry Insider were cautiously optimistic about the proposed changes, others in the industry have voiced their concerns, particularly about how Councils will respond when new products come to market – and where liability lands when products or systems fail.

Echoes of the Leaky Building Crisis are still ringing in the ears of many in the construction industry; how products can meet a particular standard to the satisfaction of Council is a key consideration.

For example, what does it mean to have a ‘compliant product’ (that demonstrates compliance), vs a system that is ‘able to comply’?

A compliant product comes with documented proof (via testing or certification) that it meets the relevant standards without needing additional verification on the project.

Whereas a system that is able to comply doesn’t have pre-approved, certified products but can achieve compliance with the NZBC if all elements are correctly designed and installed according to the requirements of E2/AS1. In this case the responsibility for ensuring compliance falls more heavily on the correct application of the system.

So, some products are easier. A tap that meets suitable international standards is a no-brainer. But product categories, such as the ones that were central to the Leaky Building Crisis, we all know can come with complexities, including installation methods, approved sealants and flashings, fire ratings and more. And not only do these products have to be individually appraised as suitable, they also have to work together as a system to be compliant.

As one contractor said: “A cladding that has a comparable standard in the EU might seem ok, but how do you install it to be compliant with E2-AS1? If you can’t demonstrate that, then it’s not going to deliver what the Bill is looking to achieve.”

Another contractor working in Passive Fire added that he’s planning to stay with the tried and tested. “Council don’t like having to do engineering judgements if products are not used in the way tested,” he says.

“If there is a standard tested system, you’ve got to use that system. But if there is no system available, you’ll need the Council to make an engineering judgment. Especially when completing work in an existing building with multiple services through one area and nowhere else to go.

And at the moment Council will only recognise systems that have made it onto the FPA website,” he says.

Another supplier said that in these trickier products and applications, the price factor is a long way down the list when assessing what product to use, and he believes there won’t be a huge amount of change in those areas.

When asked about the potential benefits of the new Act, he says “Everyone focuses on pricing, but things like being tried and true, the availability of training in installation methods, stock delivery and technical backup are all key factors that are likely to win out in the end.

“There are costs and risks of retraining with a new product also, and builders are shy of taking on any more risk than they need to.

“New Zealand is a long way from the rest of the world, with a small population that is geographically very spread out. So, I can’t see many suppliers on the other side of the world making a big commitment to this market.

“Some builders will potentially take the risk to get a lower cost, but ultimately, who is responsible when things go wrong?” he said.