In 2020, the New Zealand Government began consulting with the building and construction sector on the Whole-of-Life Embodied Carbon Reduction Framework – an initiative that aims to enforce mandatory measurement and reporting requirements, and eventual caps for embodied carbon in buildings.

The framework requires builders to report embodied carbon as part of the consent process, with compliance to carbon caps mandatory for building consent. However, unclear caps and regulatory details pose challenges for businesses already dealing with operational complexities.

While some industry sectors support the framework, concerns have arisen about potential cost escalations and regulatory challenges. Industry concerns include the lack of a standardised method for embodied carbon assessments, leading to uncertainty.

Although the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) provided technical methodology in early 2023, it did not fully address these concerns. The proposed timeline – mandatory reporting by 2025 and carbon caps by 2026 – is seen as rushed and unrealistic, especially for smaller businesses facing increased compliance costs and operational disruptions amidst an uncertain economic climate.

Industry Insider spoke with four leaders in sustainable construction to get their thoughts on the proposed framework and implications for the sector.

Shalene Gray: Board Chair for Precision Construction Limited

Carbon Precision

Shalene Gray: Board Chair, Precision Construction Limited is passionate about adopting improved construction methodologies to better benefit the environment and comes at the subject from long experience in construction.

Precision has a 40-year history and focuses on high-end residential homes and community developments, including social, affordable, and private multi-unit developments.

“By adopting modern methods of construction and materials, we apply a ‘construction conscience’ and optimise methodologies for a whole-of-life footprint. We try to lead in delivering solutions with our clients, and we’re known for our innovation and ability to bring change,” she says.

Gray emphasises that Precision is on a deliberate journey to better measure and articulate their environmental impact.

Bader Drive and Ventura Street House Development

Precision was proud to work on the Bader Ventura Passive House Project with Kainga Ora, a groundbreaking sustainable housing initiative providing energy-efficient living spaces with ultra-low energy consumption and reduced greenhouse gas emissions. Key achievements include a 90% reduction in heating and cooling energy use, a 70% reduction in carbon emissions, and affordable housing for 50 families.

“This project was innovation at its best. Social housing where tenants pay just a dollar a day to heat their homes, leading to better health and economics for residents.”

Bader Drive and Ventura Street House Development

“It took a lot to bring it to life. It does take committed leadership and collaboration with your clients to implement innovative change. And that’s why for mainstream industry, that change can be a bit slower – because people look a bit more after the here and now, versus the future, especially in current market conditions,” Gray said.

Gray is passionate but also pragmatic, with two feet on the ground when it comes to reducing carbon in construction. But she’s also keen to be part of the solution going forward.

“We’ve got a lot of New Zealanders struggling to afford to buy a home now, and there’s a lot of components, processes and regulatory changes adding a lot of cost,” she said.

“This year I’m involved in an industry initiative to drive a greater focus around reducing unnecessary time and cost in industry requirements. This can be achieved whilst also focusing on where we want to take our environment and social positioning. It is exciting to think there are good choices and methodologies the industry can use to be better. And that’s what we’re committed to,” Gray says.

Precision has chosen to adopt the use of High Performer Building endorsed products which offer excellent quality and durability whilst also being environmentally sound.

Bader Drive and Ventura Street House Development

“This is where we’re just beginning to work with Ministers, to say, “Well, let’s talk about what regulatory change is coming. Let’s have a good look at that, with the collaboration of industry leaders,” and think, “Okay, if that’s the outcome we want to achieve, what’s the best, and most pragmatic way to get there?”

So, what should builders and construction firms be doing to prepare for new environmental regulations? Gray emphasises the importance of education.

“You have to educate yourself and seek out the necessary information. For us, it starts at the business planning stage with our board, CEO, and executive team. This mindset then gets rolled out with our people. It’s not a special division but just part of doing good business,” she says.

Externally, Gray believes in the power of public-private partnerships to achieve better outcomes. “We’re talking with ministers about collaborating for better results. Regulatory changes need to be pragmatic and not drive up costs. True collaboration is key to finding smart ways to reduce whole-of-life carbon without unnecessary expenses for the end homeowners.”

Kim Aitken: Founder of the Truss House

Bridging the Gap

To achieve New Zealand’s carbon targets, sustainable housing entrepreneur Kim Aitken of Truss House says the Kiwi industry needs to go “almost from zero to a hundred.” However, as she learned when working in Canada, a more gradual legislative approach is more likely to arise from proposed legislation.

“Personally, neither is easy,” she says. “When I was going through all those step changes, I found it super disruptive because you just get your head around one principle and figure it out, and then you’re already talking about the next change.”

Aitken is on the Industry Working Group that was recently part of the Construction Sector Accord. Before moving to New Zealand from Canada, she specialised among other things, in structural design of steel pile foundations and worked on a national retrofit solar program, analysing roof systems across various house ages. She then founded Truss House, a sustainable, prefabricated building system and brought it to New Zealand.

“The building system I developed was in response to going through that process and realising there’s a way to do this that isn’t super disruptive. Truss House is a solution for offsite productivity, lower cost and baking in that carbon response,” she said.

Truss House Enscape

Aitken believes the Kiwi construction sector has a lot to learn about carbon. “Based on what I learned in Canada, I would say the step change process that New Zealand needs to take is quite the mountain to climb,” she says.

“Working in really harsh environments shines a different light on the challenges of insulation and moisture in the built environment. You don’t get a lot of room to make mistakes with things like managing moisture, managing air tightness, or doing the installation wrong because there’s an immediate feedback loop.

“When we would walk around buildings in minus 30 with a thermal imaging camera to ensure the installation was done correctly, you learn very quickly the importance of those factors. There was no choice but to really get into the science behind it,” she says.

Aitken empathises with those in the construction industry because understanding high-performance and sustainable building means taking people who work with their hands and are driven by a craft and putting them into a science environment.

“I think it’s quite a barrier. 50% of the trade base globally – as in New Zealand – is over the age of 50. We’ve got people who’ve been doing the same thing since their mid-teens, and now we want them to learn all the principles of high-performance building, apply them on-site, use new materials, use new methods. It’s a massive shift and change.”

“And it’s a skill that is really difficult to learn on the job. It’s a scientific approach to building, so if it’s not already on the worksite, you can’t just incrementally change bits and get there. To get to carbon zero, you’ve got to start with everything in place.

So, is it almost impossible to build a proper low-carbon, passive house on site from scratch?

“I would say it is difficult and challenging to get it right and systemisation is a real key to that process. But it is possible,” she says.

But it isn’t all bad news for Kiwi builders.

“We have to recognise New Zealand is very unique. Much as it doesn’t get talked about, the New Zealand builder already uses prefabrication every day in the roof truss and pre-nail wall combination.

Truss House Classroom render

“I think a pre-nail wall is used in 90% of residential houses in New Zealand, 60% in Australia, and at the time in Canada, it was less than 10%. So, Kiwi builders are really familiar with a panel product coming to the site – there’s the logistics, the layout, the fit… There’s a lot of knowledge already within the Kiwi trade base on how to execute a panelised system to get a house constructed.

“While there is a significant advantage in the mindset shift, it’s not as massive as in the Canadian context, where most builders were still hand-framing on site and creating openings and laying out walls from scratch. The story that rarely gets talked about is: ‘We’re already doing it, let’s do it slightly differently or with a higher value product,’” she says.

Aitken’s Truss House concept is designed to provide a system for building firms to achieve carbon targets while being intuitive about how it is built – taking the idea of the prefabricated roof truss, which every builder knows how to install, but extending it right down to the ground.

“The use of familiar products and skills is key. We had a lot of success in reducing overall trade time by 40% for builders and 20% for plumbing and electrical work. At below-market cost for Homestar 7 or 8 compared to code-minimum homes, we’re solving a significant problem for many builders who need or want to move into sustainability early. They can get set up, learn the principles, and upskill their trade base,” she says.

Aitken believes it is systemised building models like Truss House that will help to bridge the gap in knowledge between the craft-based industry of the past and the carbon-focussed industry of the future.

“I think we’re one of the few companies that understand if we don’t make this achievable for trades to adopt, then with the best will in the world, this is not going to be an affordable process for many people,” she said.

Lindsay Wood: Director for Resilienz

Clearcut Solutions

Lindsay Wood, MNZM, Director of Resilienz, is a leader in environmental advocacy and climate change awareness. With a career spanning over 40 years in architecture and construction, Lindsay has transitioned to focus on climate change and developing strategic climate solutions. His contributions include collaboration with key environmental bodies, experimental designs, and presenting at major international conferences.

Wood has developed an advanced carbon assessment software tool called Clearcut® – a project calculator designed to empower architects, designers, and builders to make informed decisions by estimating and comparing building costs and embodied carbon emissions.

Wood considers the carbon legislation coming for the industry in many ways already overdue for New Zealand. “BRANZ did some internationally acclaimed research on typical New Zealand houses in 2020, assessing how much carbon could be used throughout the building’s life to be compatible with the Paris Agreement. They found that even the best houses built in New Zealand used up their lifetime carbon allowance before anyone had even moved in.

“You’ve got maintenance and all the energy used in heating and cooling, and suddenly we’re far short of where we need to be. So, we have to think in terms of reducing our buildings’ carbon footprint by 80% to 90% – which is a huge ask,” he says.

Wood believes that many worthwhile climate initiatives, like thermal insulation, save long-term but cost more upfront. “I’m personally a great fan of government subsidising that, maybe through low-interest loans, so people can, for example, afford extra insulation,” he says.

Wood suggests that the coalition government might shift away from regulating carbon as part of the building consent, favouring self-regulation, possibly including tools like Clearcut. “I’m in favour of people managing it themselves, but not of self-regulation. That won’t achieve the necessary carbon shifts. It will be a softer option for the building industry.”

Wood highlights New Zealand’s challenge of reversing the trend of building better buildings that fewer people can afford. “I think we’ve reached a point with the H1 code where we’re going over the top. I’ve spent time in Germany, where some researchers say they’re using more insulation than the energy equation justifies. The energy of the insulation can exceed the energy saved by being there,” Wood says.

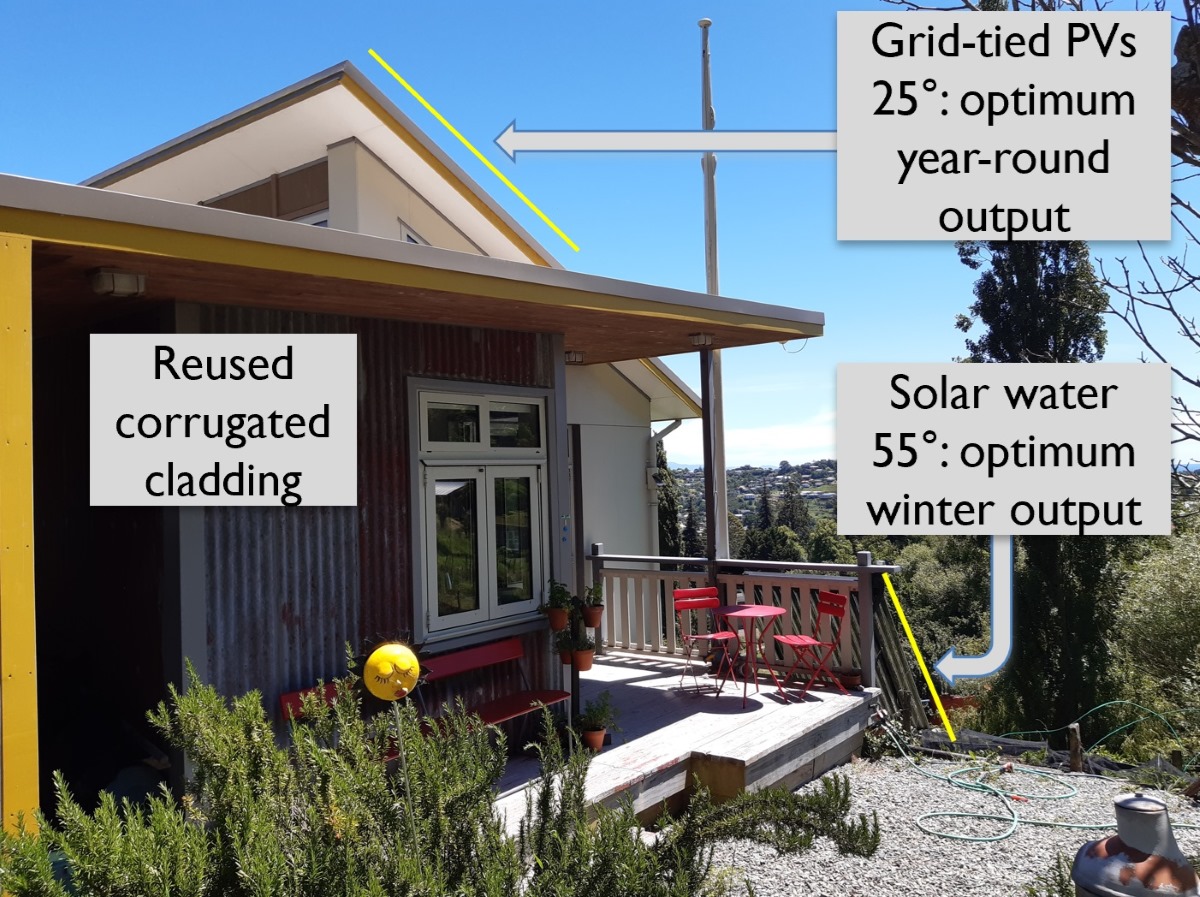

The Woodshed by Lindsay Wood

Maintaining balance is crucial if current guidance is to work. “MBIE says they want pragmatism – which makes sense – and the current government will probably lean towards pragmatism. I’m not opposed to that, as long as it’s based on sound data.”

Wood agrees with BRANZ that building smaller is a key. “Our houses have almost doubled in size over 60 years for a three or four-person family. Designers need to design better small spaces and discuss this with their clients. We’ve celebrated big, flashy designs for decades. Now, we should celebrate efficient designs that use materials skillfully, like Scandinavian design.

Should architects virtue-shame clients into smaller homes? “I don’t like framing it as virtue-shaming. It’s not constructive. Nobody builds to be a villain; it’s what we’ve grown up with and seen in media. Our role as architects is to grasp the climate reality, get good at explaining it to clients, and show that nice houses can be affordable, climate-friendly, and easy to maintain,” Wood says.

And it’s not just the build that should be considered for its carbon. Deconstruction has huge potential for sustainable improvement.

“I think we will be surprised in five or 10 years how we are building for buildings to be deconstructed and building them out of much more standardised components. I think in Europe, for example, they’ve got 20 standard window shapes that cover 99% of everything, allowing for easy reuse when buildings are taken down, which helps the cost, it very much helps the carbon footprint – but it also means we’re going to need demo yards on steroids,” he says.

Wood says a challenge is that the conversation on carbon is so abstract. “How do we make it tangible? Farmers might know the emissions from a cow’s burp, but the average architect or builder might not know the carbon footprint of concrete. We have a long way to go.”

Quoting Australian climate specialist Mark Howden, Wood’s final word is; “The climate crisis is escalating, and we’re not doing enough. If we don’t change our ways of our own volition, less palatable change will be forced upon us.”

Jane Henley: Innovation Evangelist for Aurecon

Process Driven

Jane Henley has been a global visionary in sustainable and green building standards and economics for more than 25 years, influencing business, finance, and government action in both developed and developing nations. “Where sustainability meets innovation is my sweet spot,” she says.

In recent years, Henley has been working with MBIE on the Construction Sector Accord, but now, with the Coalition Government abandoning that initiative, she’s returned to consultancy with Aurecon focusing on the challenges of productivity, innovation and reducing carbon in the construction sector.

Henley says sustainable construction comes with its own challenges because the building industry will only deliver what’s been asked for. “But at the moment, that type of low carbon home is costing a bit more. We need to change our view of the cost-value equation of paying a bit more for the house up front, rather than bearing a higher operational cost over its lifespan,” she says.

Enscape Laneway Apartments by Truss House

Henley says some companies are stepping up and showing what needs to be done.

“What Fletchers have just shown us with their recently unveiled LowCO home is that we can do it today. Our challenge as a sector is how do we bring that forward so that we’re not having energy crises like we had recently when everyone was told to turn off their heaters?”

Henley believes the downturn in the New Zealand construction sector will likely drive change in how the industry adapts to low-carbon construction, with different models of pre-fabrication filling the gaps.

“A lot of our skills are going offshore. We already had a skills problem when the market was hot, now they’re all going offshore to Australia and other places. When the market picks back up again, we’re going to have a massive skills problem.”

So, Henley suggests moving the house construction part to places where the people are, rather than the other way around. “Projects like BuildSmart in Huntley and Palmerston North have large onsite manufacturing processes where people can work 24/7. Workers can turn up to the same place, they don’t have to drive across town, the carbon footprint of driving is lower – it’s more attractive to a diverse workforce, especially women and it opens up opportunities for different types of people coming out of school, which is super important.”

Henley believes that building in a manufacturing environment also delivers a higher-quality product. “You know exactly what’s going into the building. You’re designing it properly to reduce the waste, which reduces the carbon footprint.”

She strongly believes this type of approach can help New Zealand achieve its carbon targets, whether in a factory environment or an onsite factory next to where the houses are being built.

“Simplicity Living has a big site where they’ve set up an onsite factory. They have a very lean, agile approach to their manufacturing, so they get fewer delays, exactly the product they want, and highest performance at less cost. Changing to a more controlled process-driven approach helps meet these targets by taking out costs and increasing quality,” she says.

But if mass production is the answer to carbon reduction, that doesn’t bode well for the small builder, who must see this as incredibly daunting? Henley says they should see it as an opportunity as well. “The factory that built that house also produces wall panels, floor panels and roof panels, so the builder becomes an assembler. They don’t do the bespoke work – they become a sophisticated assembler of parts.”

Regarding major home renovations, Henley notes that Europe’s energy performance rating system could be a model for New Zealand. “When you buy your house, you’ll know how many megawatts a year your house uses and the cost of that. It’s like a star rating on your fridge. We need a common language around performance and what’s in our houses. Many houses in New Zealand aren’t up to code, and we have to manage that reality to avoid people having stranded assets.”

So, what is Henley’s advice for builders facing these changes? Understanding their current practices and how they stack up against upcoming caps is important to begin with. “They probably need to get someone to do an energy model on a site they’ve already built and see where it stacks up. Then they have a baseline and can look at what incremental changes to make to stay ahead of the curve.

“That’s why these changes are coming in slowly. We know that shelter and safety and getting houses built is as important as meeting our climate commitments. We’re not trading people for better houses.

“I think people in the industry need to be going: “Hang on a second. Where can I do things better?” Let me take a look at my own process. Let me see what I’m doing today and see what my options are,” Henley says.