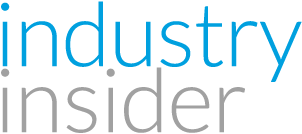

Kloof House, Cape Town, South Africa

Distinguished South African architect and key partner in renowned design studio SAOTA, Philip Olmesdahl has contributed to the world of architecture through his distinctive and innovative designs.

Born and raised in Durban, Olmesdahl moved to Cape Town to join Stefan Antoni Architects in the mid-eighties, going on to restructure the firm along with Greg Truen into SAOTA, an award-winning international architecture studio that has expanded its influence to 86 countries, with projects in over 193 cities.

Olmesdahl brings a nuanced approach to his work by focusing on the interplay between the project’s location and the built environment to create unique designs such as the award-winning OVD 919 Cape Town house and Uluwatu house in Bali.

Throughout his career Olmesdahl has emphasised the role of an architect is more than just a designer, but as a communicator, organiser and project manager as well. His personal design style is constantly evolving as he views every project as an opportunity for unique creativity, avoiding repetitive aesthetics in favour of projects that fit into diverse contexts, sites, and climates.

Uluwatu house, Bali, Indonesia

He says an emerging challenge to working across so many countries and cultures is in the ‘sustainability conversation’ and how that as a concept can vary around the globe.

“The South African market is not as sophisticated as Australia or New Zealand in terms of regulatory requirements or adequate available expertise,” he says. “Unfortunately, it is defined by high construction costs and fairly low technologies and skills, a combination doesn’t leave an awful lot on the table in terms of building responsiveness to sustainable measures.

“So although South Africa has great objectives to design in a more sustainable way, the expertise needed to meaningfully realise that must come more from our international experience rather than our background in the South African market,” he says.

Olmesdahl says that for projects in environments such as Europe, Australia or New Zealand, local regulations bring sustainability firmly into the equation. “However a lot of other regions and maybe surprisingly even the US and the Middle East, have regulations that aren’t really all that demanding,” he says.

SAOTA sees itself as a practice very skilled with passive and responsible design. Projects are typically medium-sized and single residential, along with smaller-scale hospitality and multi-residential projects – the part of the market not particularly well-supported by sustainability consultants and systems. It is the projects in foreign markets that allows SAOTA to demonstrate their commitment to sustainability.

Double Bay, Sydney, Australia

“If you increase that project size to 10,000 to 15,000 square-meter schemes, whether they be multi-residential or commercial, there is a lot more support, budget and demand,” he says. “But that is not the trajectory that we’ve come from, so we try and focus our designers on objectives that don’t necessarily fly on the banner of sustainability, but rather to use intuitive skills that would result in a building being more sustainable,” he says.

So, the SAOTA team focusses on factors such as: does the building have adequate shading? Does the building respond well to its context? Does the building have other passive measures that can exist in the absence of sophisticated water heating systems, sophisticated PV systems, sophisticated electronic control systems?

In addition, SAOTA rigorously seeks options to introduce sustainable approaches through a project’s concept design and design development within the applicable and enormously varied local regulations.

“Many of the areas we work in South Africa have particular requirements in terms of the development scale, responsiveness to the inclusion of adequate landscaping, approaches to density, and approaches to efficiencies on sites.

Kloof House, Cape Town, South Africa

“So that’s provided a platform for understanding sustainability from an urban point of view in terms of using sites appropriately, using sites with the objective of density, building buildings that have a layering of passive measures like PV and water heating and a better approach to insulation,” he says.

Technology’s Key Role

In terms of the design process, Olmesdahl says that in the past, technology was the mechanism that helped you to present and publish your ideas, but it is now central to the development of the design concept.

Technology has played a key role for SAOTA and a factor in its international success because Olmesdahl sees it as a lens that enables new or different design approaches to a project.

“As a practice, we have always invested a huge amount of energy to enhance technology and that’s played a massive role in terms of the development of our foreign work and allows us to interact with our clients without having to sit across the table,” he says.

“Working in different time zones and cultural environments has allowed us a valuable depth of understanding over regional site constraints and restrictions. If we can get information about the site, we can put it into either Virtual Reality or other more ordinary platforms to help the client understand the project and its potential,” he says.

Colina, Madeira, Portugal

“From that we can get a better sense of the impact of unique controls and other factors and can build them into the models and the three-dimensional environment faster,” he says.

Olmesdahl says that being supported by technology, 3D-printing programs and the like, allow you to move very quickly through the development of a project. He’s frequently talking to the SAOTA team about how the design process is no longer perfectly linear, and it can have many unexpected outcomes.

Utilising tools like VR, and AI, the SAOTA team can assess multiple responses to a site from a program and planning point of view.

“You can try different things quite quickly and assess them in a three-dimensional environment and really map out advantages or disadvantages between different schemes in a much easier real-time way,” he says.

Olmesdahl says that things are changing fast and the set of skills that most of the graduates have now, specifically their knowledge of technology and platforms is completely different because of these new tools. But he warns that tools like AI, Virtual Design, Machine Learning, and Virtual Reality are challenging the traditional role of the architect.

NorthGarden – DDS, São Paulo, Brazil

“I’d love to say there’s a lot of excitement about AI, but I think there’s also a much bigger concern about it at the moment. Its impact is already quite profound.

“There are programs that can generate multiple responses to a project with fairly limited input from the designers. And that way, of course, it meaningfully kicks a project off and changes the initial stages that a designer would’ve applied.

“And then, of course, on the tail end, there are things like Midjourney, where particular characteristics can be put into the platform and it can spit out various design options, whether they be just superficial aesthetic options or alternative form options,” he said.

Olmesdahl believes that presents some major risks to individuals and studios going forward.

“Where a sophisticated client wants a project designed by a particular individual or studio, of course, they’ll stay with that approach. But in many instances, unfortunately, clients just want to maximize what’s available on the land. And they just want to put an aesthetic on the building that one can create through AI. I think that’s going to result in some parts of the market losing out by not having an edge anymore because AI, of course, can provide that.”

Park @ City Walk, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

On the positive side, Olmesdahl says the platforms are going to offer a lot in terms of efficiencies to studios and hopefully help design more intelligent and more appropriate buildings.

“From our side, we are committed to bringing AI into our workflow in an appropriate way. It really revolves around design options, developing a multitude of responses to a site or a problem with AI, and hopefully using humans in terms of assessing which designs are most appropriate. And hopefully, providing a visual DNA to the building that’s defined by characteristics that AI can’t quite achieve just yet,” he says.

Join us at Design Experience this September to hear Philip Olmesdahl present: Light Space Life, and how these three core ideas have shaped the work that has established SAOTA as an integral part of the global architectural landscape. To hear him live, see here for dates and times in your region.